Steven ten Thije, 13 August 2018

Looking and seeing – thoughts on the work of Theresa Rijssenbeek

Why paint? In all its simplicity, still a difficult question. In an age when images appear in thousandfold at the simple touch of a smart screen, why toil with a brush, pencil or pen? For the painter, however, it is not a question at all. They know why. The answer comes to them over and over again, every time the brush touches the canvas and the miracle of creating an image is repeated. But the non-painter keeps on searching. Perhaps you feel the simple autonomy of the painting, yet still you look for language to make that autonomy comprehensible. As if fascination with the painting itself is not enough. It has been my task for years to find those words, in this case language to encapsulate the work of Theresa Rijssenbeek.

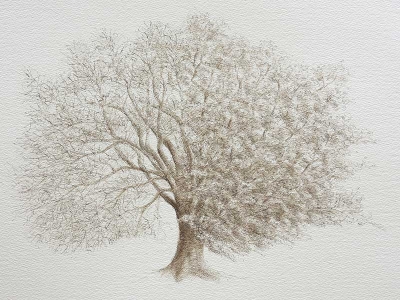

It all starts with two words: looking and seeing. We think they mean much the same thing, but there is a subtle difference between them. Or, to put it better: I would like to introduce a subtle difference between them, to help to unlock something linguistically from the work. Looking is what we do most of the day, whenever we are awake. Subconsciously, we continuously process visual impressions in order to decipher their most relevant content. Where is the door? Is it raining outside? Oh, a lamppost: step to the left. Without thinking much about it, all day we are processing impressions to make it possible for us to move through the world without to stumbling over every obstacle we encounter. Only occasionally, suddenly, like a flash of light pulling us out from the daily grind, does something pierce the stream of impressions and become an image. For the non-painter, that is often a dramatic thing like a sunset or a beautiful mountain ridge. Look at those colours! Aren’t they beautiful?

It is when something suddenly detaches itself like this from the permanent visual violence of the world that looking becomes seeing. The difference is one of gradation. The moment when something originally unremarked in the margins of our attention first impinges on our consciousness. When something is no longer simply part of the surroundings, but is assigned a quality of its own. The colour of a flower, the structure of a tree trunk, the rhythms of green hues on a mountain ridge: for a moment they acquire a value of their own. That is the moment when we are no longer looking, but seeing. When an image can appear.

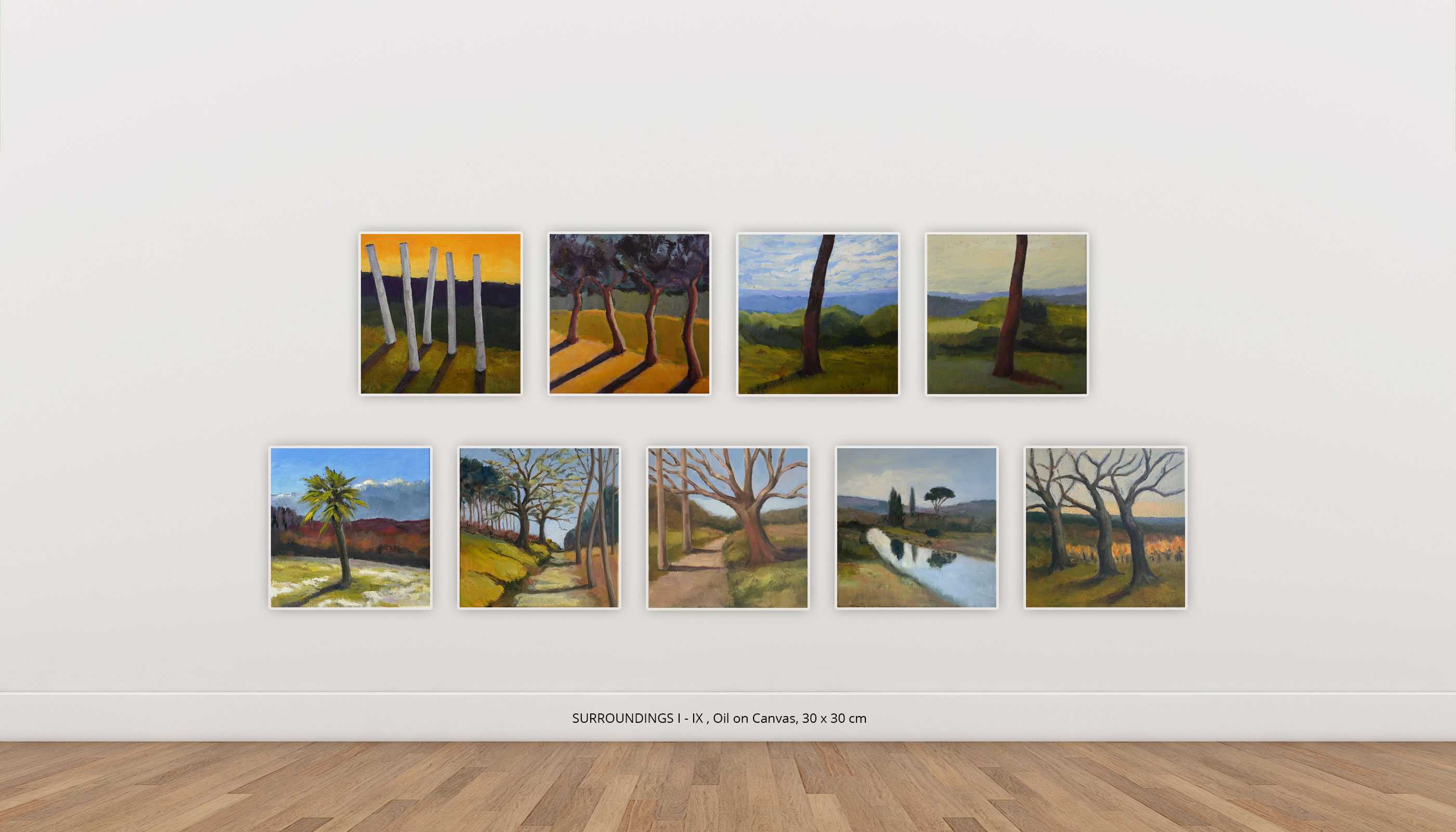

A painting by Theresa Rijssenbeek is images appearing out of moments of seeing. At just the point where looking ceases and something displays its own intrinsic quality. But those are not moments then caught in the click of a shutter. The moment of seeing is not captured, killed and preserved like an exotic butterfly. The seeing begins a process in which, sketching and painting, Theresa seeks out the painterly equivalent of the moment. Although not in such a way that the “essence” is expressed. (It might be, but that is not necessarily the goal.) No, the question for her is simpler. Can I distil something from a moment of seeing that is able to become an image in its own right again, and so make new seeing possible? She thus paints not an image of nature, but an image in parallel with nature.

The image unfolds gradually, in the act of painting. In the movement of her hand, her arm, her brush. In the paint being absorbed into the canvas and creating structures which evoke a visible tension. Your eyes move across the surface of the painting and register both connections and contrasts. Liberated from the chore of mapping the world for your day-to-day navigation through it, you can calmly follow the movement of your eyes as if they are dancing their own dance where body and world meet.

The work I am looking at now, sitting in Theresa’s studio, consists of a white rectangle measuring, say, 120 by 150 cm. It is upright, with an oval shape in the middle, made up of different greys – slightly lighter at the top and bottom than in the middle. Below and between these grey fields lie black lines, like narrow, swirling leaves. You might easily imagine that the branches of a tree, or perhaps even some kind of flower, were the original inspiration. But whatever it was, the painting only uses that as a starting point for something new. As you look, relationships start to arise between the stripes and the white-and-grey background. As if they have something to say to each other, the stripes swim one alongside the other, hidden at one moment and then brutally visible the next. If you wanted to, you could give each line its own name and personality, as if they were characters in a book. The grey space between them is their world, first swallowing them up and then embracing them again. The painting is an image in which something is happening of its own accord, something I as a seeing viewer am allowed to be present at just for a moment.

Seeing requires peace and time. You need a certain silence in order to be able to surrender yourself to the event of the image. The painting, in its all craftsmanship, helps with this. Unlike with a mechanical image, it is quite natural to retrace the movement of the brush and so taste with your eye all the relationships concealed within the image. That may also be a modest answer to the question “Why paint”? The act of painting, and its result, help the trained eye, but also (perhaps even especially) the untrained one, to move from looking to seeing. To a seeing that occurs not just sporadically in our daily journey through the world, more accidentally than on purpose, but one which awaits you calmly in congealed paint, hanging on the wall, to draw you time and again into the world of the image. Making the painting a kind of special, yet everyday, medicine against indifference. Because, fortunately, the painting is also contagious. Once you have seen with the help of the painting, as you walk through the world you cannot but help suddenly experiencing that pinprick of seeing in other places, too, as when a simple leaf or flower changes from being part of the surroundings into an image in its own right.

Steven ten Thije, 13 August 2018

Born in the Netherlands, 1951, theresa rijssenbeek spends a large part of her youth near the North Sea coast. Dunes, woods and the sea are the setting of her early life. She draws what she admires. When she lives for three years on the tropical island of Curacao (late 70’s) she is overwhelmed by the colours and nature. She starts painting using oil and water paint. Her first exhibition is a great success. Back in the Netherlands she studies at the prominent Royal Academy in The Hague and becomes lifelong friends with head of department Rien Bout who also coaches her. Her professional career as a painter begins in 1990, with yearly exhibitions. The city of Delft commissions a 10 metre high mural painting in a housing project. Not much later, theresa’s work is also seen on Dutch television.

Born in the Netherlands, 1951, theresa rijssenbeek spends a large part of her youth near the North Sea coast. Dunes, woods and the sea are the setting of her early life. She draws what she admires. When she lives for three years on the tropical island of Curacao (late 70’s) she is overwhelmed by the colours and nature. She starts painting using oil and water paint. Her first exhibition is a great success. Back in the Netherlands she studies at the prominent Royal Academy in The Hague and becomes lifelong friends with head of department Rien Bout who also coaches her. Her professional career as a painter begins in 1990, with yearly exhibitions. The city of Delft commissions a 10 metre high mural painting in a housing project. Not much later, theresa’s work is also seen on Dutch television.